Towards the end of last year, the UK High Court delivered a significant judgment in favour of Thom Browne in a high-profile trade mark dispute with sportswear giant adidas. The case centred on the validity of adidas' famous three-stripe trade marks and the alleged infringement by Thom Browne's "Four Bar Design". The court found that several of adidas' trade marks were invalid due to lack of clarity and precision, and held that there was no likelihood of confusion between the two designs. The decision was somewhat notable as the Court decided to diverge from previous decisions of the EUIPO on validity and ultimately conducted its own independent analysis of the adidas trade marks.

The case carries a significant warning to brands, and in particular those looking to protect trade dress, making clear the importance of careful trade mark applications. While most brands will regularly review their portfolio, they should be considering the precision of their trade marks in light of this judgment and the recent Skykick judgment.

We discuss the Court's findings in detail below.

The Dispute

Adidas has registered trade marks for various iterations of the three-stripe design in multiple jurisdictions. In an earlier case, adidas filed legal proceedings in New York against Thom Browne (TB), alleging that TB's use of a four-stripe design infringed adidas' trade marks. The New York court ruled that TB's signs did not infringe adidas' trade marks. In 2021, TB filed legal proceedings in London to revoke adidas' trade marks, arguing that the marks were unclear and left designers confused about their scope. Adidas countered alleging that TB's use of the four-stripe design constituted an infringement of its trade marks.

Key Issues and Court Findings

- Revocation of adidas' Trade mark

TB contended that adidas' marks included vague descriptions and confusing references to images, which made it impossible to identify the scope of the mark clearly. To register a trade mark in the UK, the mark must be represented in a manner that enables the registrar and the public to determine the clear and precise subject matter of the protection afforded by the mark. The judge meticulously examined each mark and found that the use of descriptions such as 'substantially the whole length of,' 'stripes running along one third or more of the length of the sleeve,' and 'generally used vertically' were too broad and likely to leave the public and competitors in a state of confusion regarding the scope of the marks. Conversely, marks with descriptions referring to the pictorial representation with comments such as 'as illustrated in the image' were found to be valid where the scope of the mark was confined to how it appeared in the reference image and did not suggest that the image was one iteration of many possible permutations. Ultimately, the court found that eight of the sixteen adidas marks failed to meet the identification requirements under the Trade Marks Act 1994.

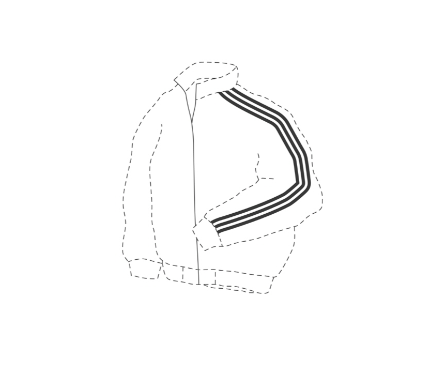

Tracksuit Top Mark:

Invalid - Three trade marks had been registered for tracksuit tops with descriptions which referred to stripes running along "one third or more" of the sleeve, or running down "substantially the whole length" of sleeves, legs and/or trunks.

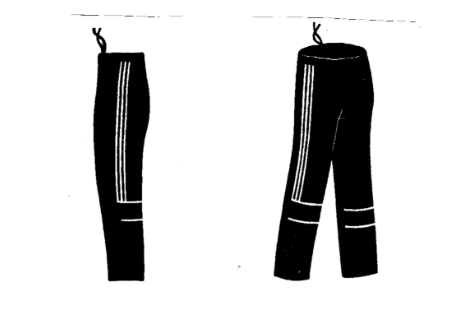

Tracksuit Bottom Mark:

Invalid – the description for the above mark referred to stripes running along "one third or more of the side of the trouser or short" and also stated "as illustrated below", referring to the above image as an example only, and leaving room for various permutations of the mark.

Tracksuit Bottom Mark:

Valid – the description "The mark consists of three parallel stripes going down the outside legs of the garment together with two horizontal stripes going round the back of the knee portions, as shown in the accompanying illustration" was found to be sufficiently clear and precise.

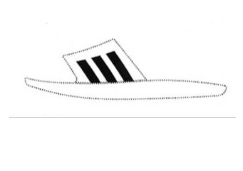

Slide Marks:

Slide Marks:

Valid – the description "three parallel equally spaced stripes applied to the bandage of footwear, the stripes extending from the base of the bandage, as shown in the representation attached to the form of application" was found to be sufficiently clear, and the reference to the pictorial representation clarified that the scope of the mark was limited to what appeared therein.

Cap Mark:

Valid – the mark was registered in respect of caps. The description "the mark comprises three stripes applied on a cap visor, as shown in the illustration, the shape of the cap as such does not form part of the mark" was found to be sufficiently clear as the reference to the illustration made clear that the mark is limited in scope by reference to the illustration.

Bag Mark:

Invalid – the description referred to stripes "generally used vertically", and stated "The example shown in the representation of the mark demonstrates the relative proportion of the mark in relation to the product" both of which were considered too broad, and implied a multitude of different forms.

2. Whether TB's four-stripe design infringed the adidas Marks

2.1 Trade mark Infringement under Section 10(2) TMA 1994

In its counterclaim, adidas alleged that the similarities between TB's four-stripe design and adidas' Marks, as well as the similarities between the goods and services for which the marks were used, created a likelihood of confusion. Adidas conceded that there was unlikely to be direct confusion among consumers at the point of purchase but maintained that consumers might be confused in the post-sale context. Specifically, adidas argued that third parties who encounter the goods after sale might wrongly assume the goods to belong to adidas, as these consumers were likely to pay a lower level of attention than the initial purchaser. The judge rejected this argument, finding that the average consumer must be someone who relies on a trade mark as a badge of origin and would not display a lower level of attention in the post-sale context. The judge also noted that the positioning of the marks on the garments was a critical issue, and only when TB's mark ran vertically was there a degree of similarity. The judge found that while the overall impression of stripes with gaps is similar, there were a number of obvious visual differences, including the additional stripe used by TB, TB's stripes being 'chunkier' and appearing 'hooped,' as well as the position of the marks on the garments.

The judge found that the absence of evidence of actual confusion significant, given the long period of parallel trading between the parties. Adidas relied on a handful of social media comments to demonstrate confusion, but the judge found this evidence to be unsatisfactory, stating that the pool of comments was too small to have any real evidential value. Additionally, the judge disregarded some of the comments on the basis that there was no evidence that any of the commenters were based in the UK, none of the commenters were called to give evidence, and many of the comments did not demonstrate confusion at all. The judge highlighted that no credible evidence was produced of anyone having been deceived. Furthermore, the judge noted that the significant use of social media for scrutinizing and commenting on clothing and fashion items would have likely resulted in ample expressions of confusion if it were taking place.

2.2 Trade mark Infringement under Section 10(3) TMA 1994

A claim under Section 10(3) requires the proprietor of a trade mark to show that the public will make a link between the trade mark which is registered and the sign complained of, even if they do not confuse them and that as a result, the sign takes unfair advantage of, or is detrimental to the distinctive character or reputation of the trade mark.

The judge acknowledged that adidas had a reputation throughout the UK in relation to the majority of the adidas Marks in 2009. However, the judge concluded that the average consumer would not make a link between the Four Bar Design and the adidas Marks, when considering that the average consumer would be familiar with the adidas Marks and adidas' products and particularly in the context of the high-end, luxury market in which TB operates. Adidas acknowledged that there was no direct evidence of a change in the economic behaviour of the average consumer of goods for which the adidas Marks are registered, but suggested that this might occur in the future. The judge considered the idea that TB's use of the Four Bar Design would bring about a material change in economic behaviour of the average consumer of goods for which the adidas Marks are registered to be "hopelessly unrealistic" considering the very different target markets. Furthermore, the judge found that if TB's use of the Four Bar Design was likely to cause a genuine change in economic behaviour, there would be some evidence of that already, for example, on social media, but there was none.

3. Honest Concurrent Use

TB argued that the Four Bar Design was conceived in 2008 after adidas complained about its use of three horizontal bars. The Four Bar Design was launched in 2009 and used widely by TB since then. TB contended that adidas's delay in taking action implied acceptance of the Four Bar Design. Adidas argued that they hadn't filed proceedings earlier for 'commercial reasons' and suggested that TB's sales figures in the UK were insignificant. Addias also argued that the 'tipping point' however, was when TB released a new product range which included sportswear featuring the four-stripe design on running shorts, tops, and leggings (the 'Compression Range'). adidas argued that the test date for the honest concurrent use defence should only be assessed as of 2020 when the Compression Range was launched, and that this represented a material change in TB's field of activity and was when TB started to encroach on adidas's core market. However, the judge rejected the adidas's argument that the launch of the compression range in 2020 represented a material change in activity by TB. The judge inferred that adidas did not take action earlier because it did not consider the Four Bar Design to be an infringing use and that adidas was prepared to coexist alongside TB.

The judge accepted TB's evidence that the Four Bar Design was conceived to stay true to the brand's inspiration and that there was no reason to believe that any number of stripes other than three would be problematic for adidas. The judge found that TB's use of the Four Bar Design was honest and that TB had acted fairly in relation to adidas' legitimate interests.

4. Passing Off

Adidas also claimed that it had goodwill in its use of three stripes in various executions and that TB's use of the four-bar design constituted a misrepresentation to the public. Whilst the judge found that adidas had goodwill in the "Vertical Execution" of its Three Stripes Marks, which are well known and distinctive, only some goodwill existed in relation to the horizontal executions as at 2020 (and there was insufficient evidence of goodwill in the horizontal executions as at 2009).

The passing off claim failed however, as there was no evidence of misrepresentation or damage in relation to any of the executions which had established goodwill. The judge found that the Four Bar Design was not intended to create any connection with adidas, and there was no evidence that the public was deceived into believing that TB's products were associated with adidas, thus there was no misrepresentation to the public. Finally, the judge found no evidence of damage to adidas' goodwill. The absence of any actual confusion or misrepresentation meant that there was no basis for concluding that adidas had suffered or was likely to suffer damage as a result of TB's use of the Four Bar Design. The judge also dismissed speculative arguments from adidas about potential future damage, such as loss of control over collaboration partners or dilution of distinctiveness.

Conclusions and takeaways

The case is an interesting example of the challenges of registering and enforcing position marks, especially where those marks are fairly simple and arguably decorative. While the court accepted that adidas could protect its three-stripes, some registrations failed to comply with the strict requirements for protection. Those requirements have been more strictly enforced in the last decade, and brands should be ensuring that their marks meet the criteria for protection, and filing replacements if they might not be.

It is also interesting for the importance given by the court to the orientation of the marks, holding that adidas's rights did not stretch to horizontally oriented stripes. This conclusion, while probably a sensible limitation on adidas's rights, raises questions as to how consumers see signs in the real world. The UK Court of Appeal considered this issue in a decision involving Umbro in 2024, which is due to be heard by the Supreme Court in March 2025, and it will be interesting to see how the highest court in the land sees the issue of context.